Being raised on a farm had a significant influence on my life. As I grew up, I studied anthropology, history, and African literature. Two events deeply disrupted my early life: the family farm being sold in 1965 and being drafted into the Vietnam War in 1969. I wound up serving my time in the Air Force, where I added construction skills I had learned on the family farm. During that time, the Civil Rights Movement had an enormous impact on me, and I started to take my interests in world history, anthropology, and photography more seriously. I had always felt the pull to travel and thought that documenting my journeys through writing and photography would be fun and interesting. My NYC carpentry business was successful enough to fund my impulse to visit Africa.

My first trip was to Kenya, where I took several safaris to many national parks and the coast of Kenya, photographing people, landscapes, and wildlife. I stayed with a welcoming family with whom I developed a close relationship over the years.

When I returned from Kenya, I made large color prints and installed them in a local restaurant with track lighting. I curated the collection of photographs there for about a year and was able to show and sell my work. The exhibition was well received, and I sold almost all of the photographs, replacing them as they sold. It was a positive experience, giving me the support and courage to continue creating art. From there, I searched and found other venues willing to exhibit and sell my work.

As this new world of being a photographer opened up to me, I started writing and documenting my experiences in both Kenya and New York. It was a very transformative time, and I welcomed the change.

I was 35 years old in 1985 when I took my first trip to Kenya. I traveled with three women to Nairobi, where we rented a vehicle that took us to the small village of Machakos and then to Kituvi. I clearly remember how overwhelming I found the beauty of the land and the people. As we drove up a mountain toward Kituvi, I could see I was in a rural farming community with livestock, vegetables, and fruit growing all around. Men, women, and children were tilling the soil with hoes and pickaxes. The rolling fields and fertile land were so like where I grew up. As we passed local markets, I saw large baskets of tomatoes and potatoes piled on the ground. Women were sitting around, socializing while they waited for a buyer.

My sleeping quarters consisted of a hut with a dirt floor. The hut was dug into a hillside with roots hanging down the walls. There was no running water, no electricity. This felt like I was in a different world, but I found I liked this new place. I felt at ease and myself. I was surrounded by the expanse of the land, the deep red soil, the green foliage, and the bright purple flowers blooming on the trees around the compound. I still remember their intoxicating yet refreshing smell.

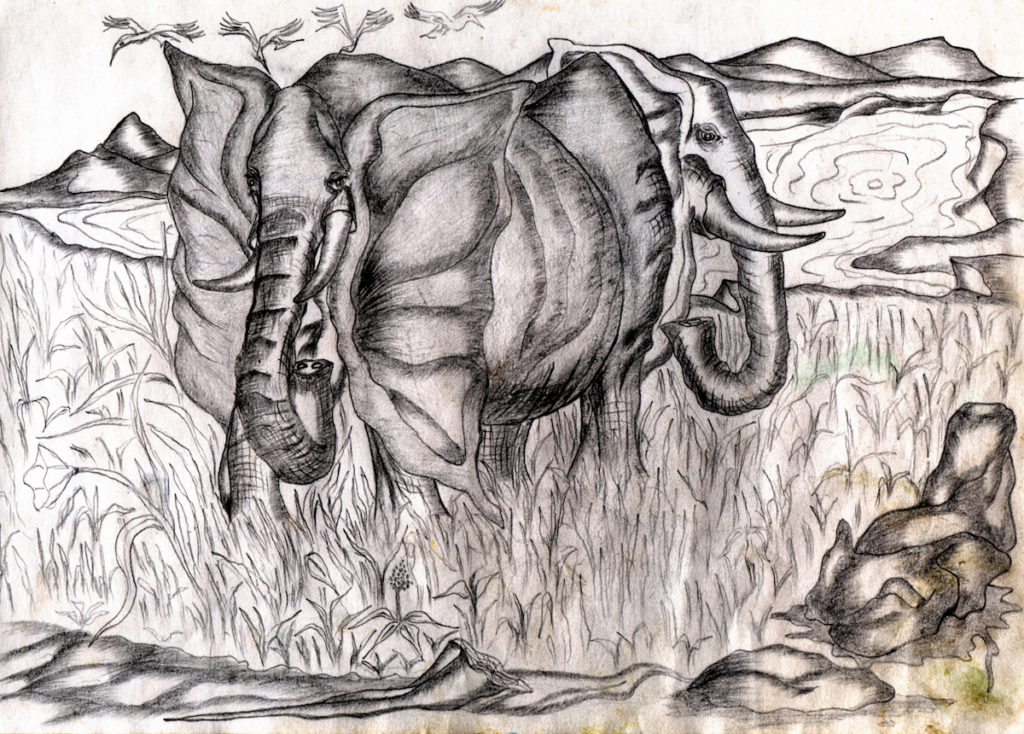

I took hundreds of photographs and kept a diary of my observations and experiences. After a short stay, we went on a long and dusty drive to the Masai Mara. The landscape was beautiful, with wide views and large herds of buffalo, zebra, and elephants. I began to wonder if I had been born on the wrong continent. I could even hear the birds sing, something I had not heard in years living in an urban environment of New York City.

Year after year, I traveled to Africa, taking breaks from my carpentry business. I kept writing and taking photographs of my experiences in Africa and showing my pictures in NYC restaurants, then galleries, and then a one-person show. The carpenter was becoming a professional artist, and I couldn’t have been happier.

The year following my first trip, I traveled back to Kenya with my 12-year-old son to visit the Kenyan family I had stayed with previously. I thought it would be a wonderful experience for both of us. Together, we built a house for the family and a place where we could visit and spend time. It was our way of saying “thank you” to them and for the opportunities to learn about Africa.

Over the years, I spent time visiting the family and got to know them and the community. When I was not operating a business in New York, I was traveling to Kenya, staying with the family, and then taking long safaris to other countries in the southern regions of Africa.

These experiences provided opportunities for me to gain knowledge about Africa and to expand on my photography and video skills. I started reading about the places I visited and writing about my travels. I interviewed politicians, clergy, and community members. I started taking courses at SUNY and reading books about history, colonialism, and social and political issues. I read novels and learned about the natural environments of East Africa and the southern regions such as Zambia, Zimbabwe, and South Africa. The beauty of the natural environments inspired me to reflect and write more. I wanted to learn as much as possible. I visited schools and spent time in villages listening to stories and learning about the lives of people and how they lived. This was a new beginning for me.

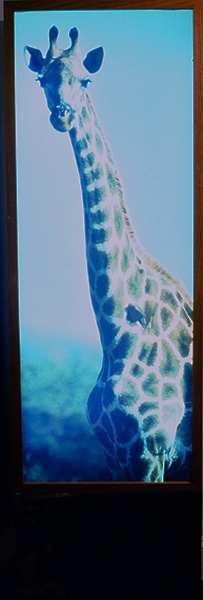

I needed to figure out a way to show my exploration to the world. I decided to integrate my carpentry skills by designing and building custom-made frames and boxes with backlighting and large color transparencies. It was here that two interests of mine came together to create something new.

Each lightbox was built specifically to match a transparency. The transparencies were made from 35mm slides and negatives. I wrote stories about each of the images, the lightbox designs, and the experiences I had with photographing the subjects. I decided to use African wildlife and landscapes for the transparencies. I referred to the lightboxes as light sculptures since the creations were integrated with a customized box, color transparency, and story. When finished, I had a collection of about 33 light sculptures of various styles and sizes.

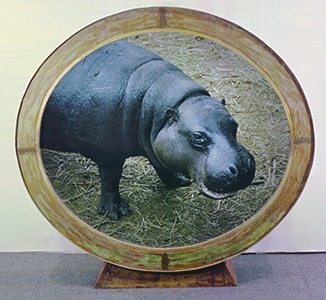

I found installation sites and locations around the suburbs of New York and in the city. Locations included storefronts, bank windows, galleries, and museums. I created a large waterproof copper light sculpture with a transparency of a hippo (55” x 66”) and installed it in the graveyard of St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery. As far as political statements, I made none and let viewers decide on their own what their experiences were as a result of the installations.

I built three tombstone-shaped sculptures with large transparencies of African hornbills, which were also installed in the graveyard at the site of the hippo. I put the light sculptures on timers so they would automatically light up at night. They faced Second Avenue and 10th Street, where everyone could see them as they walked by. In addition to being installed outside in the graveyard, the hornbill light sculptures were also used in church ceremonies.

I built an 84” tall wood light box with a large transparency of a giraffe. The light sculpture had a one-way mirror with a motion detector, so when people stood in front of the sculpture, they would see themselves, and then the backlight would turn on, making the giraffe appear. The light sculptures were also known as environmental sculptures and were built to remind people about the environment. Each time I visited Africa, I was reminded of the destruction to the national parks and the diminishing wildlife and birds as a result of climate change, overdevelopment, and the encouragement of people using the land for the expansion of agriculture. This was heartbreaking to see wildlife reduced, and the destruction of natural environments, poaching, droughts, tourism, and diseases add to this problem.

I installed a photographic exhibit at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery for the celebration of St. Francis Day. This exhibit consisted of 30 large color prints of African wildlife. In addition, the exhibit was the beginning of the Visual Arts Program at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery. The Visual Arts Program included a curatorial program and a sculpture garden in a shared gallery space. The idea was to provide an exhibit space whereby local artists could show their artwork.

As part of the Visual Arts Program, I developed a program called Kidsview, which was a hands-on photography workshop program focusing on youth. Kidsview started working with a Lower Eastside public school and eventually collaborated with a school in the West Village, adding art to the Kidsview program. I wanted storytelling to become part of the projects. Art, photographs, and writing added a much richer way of

making a cultural exchange between the USA and Kenyans. Also, I was trying to build an art and photography project within the local community of St. Mark’s Church, local schools, and art organizations. We had several exhibits at the St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery, and I selected over two dozen paintings and drawings to exhibit in Kenya. I also prepared a suitcase filled with art supplies, including paint, brushes, paper, and colored pencils.

The seeds of this project were sown in 1994 when I traveled to Kenya to meet the Bishop of Machakos, who organized 16 high schools and middle schools for me to visit. There, I gathered drawings and paintings made by the Kenyan schoolchildren.

The bishop’s idea was to connect the Kenyan students with students in New York and then build a relationship between parishes of the dioceses of New York and Machakos. Having worked with an art teacher and some West Village students, I had brought along a set of bright and colorful paintings. The Kenyan students and teachers loved them.

The bishop provided me with his deacon and a small four-wheel drive vehicle. We traveled all over Machakos and Makueni County, visiting school after school. At each school, I gave a detailed presentation about the project and displayed the New York City students’ artwork on the floor of a large classroom and sometimes outdoors. The students were very eager and excited to participate and responded by showing their own artwork. These experiences were gifts to me I can never forget.

At the church center, the bishop gave me space to mount the New York students’ art collection. I also got access to a computer so the Kenyan children could respond to their counterparts in New York. The main newspaper of Kenya, The Nation, published a story about the project and exhibition.

Back in New York, I went through the piles of the Kenyans’ paintings and drawings. The artwork of 1994 represents many of the same issues of today: drought and access to water, poaching of animals, domestic violence, poverty, and alcoholism. Because these paintings and drawings were so very different from the New York children’s artwork, I wanted to find a public place to display them and discovered a storefront space in the Port Authority Bus Terminal. I installed a clothesline in the huge display window and hung the paintings and drawings on the clothesline.

An archbishop of Kenya came to see the exhibition, as did a bishop from the New York Diocese and other church officials. I also showed the drawings and paintings at the Staten Island Children’s Museum, and both exhibits got newspaper coverage. The project was gaining traction and getting noticed. It was a success, opening up new opportunities.

These were just a few of the drawings and paintings the children and youth created.

Fast forward through more trips to Africa, more school visits, and new exhibits in museums—the artwork was now shown at St. Mark’s Church in New York’s Bowery area and even the United Nations.

The Machakos and Makueni exhibition was shown at the United Nations Headquarters, Port Authority, New York, and museums, colleges, and universities throughout the US.

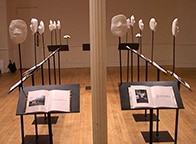

I collaborated with another school, PS 63, Lower Eastside, on an ESL project involving eight immigrants. The immigration workshop project goal was to create a collection of masks and photo diaries, capturing the stories of the immigrants.

They used cameras, old family photographs, and computers to create their photo diaries. I also captured their stories on video throughout several interviews. For many of them, it was the first time they told their stories and made an actual photo diary in English. The photo diaries were bound into hardcover books for an exhibition at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery. In addition to the exhibition, the students performed dances and read poems to an audience in the gallery space at St. Mark’s in-the-Bowery.

I then installed part of the Machakos and Makueni exhibition at the Nyack Museum, where I met a person who taught at the New York School for the Deaf. The exhibition inspired several new workshops where I used cameras, computers, and art to create a new collection of photo diaries. Several exhibitions resulted from this and were installed at several schools—and at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery.

One day, while watching a play, I noticed some students using masks in a performance. This gave me an idea on how to create a face mask workshop that I would implement in a youth program.

I took an exhibition and mask-making materials to Klerksdorp, South Africa. There, I set up an exhibition and started making masks with a group of 15 youths. The project’s focus was to capture the lives of the 15 children, their families, and their communities.

I spent several weeks with youths, traveling around South Africa, learning about their country and their lives. The mask workshops helped them bond and develop a relationship with me. It was very challenging for them to focus on themselves. They had experienced so much trauma and self-reflection, triggering a lot of painful memories. The masks were helping in telling their stories about post-apartheid. Some of the stories were about discrimination, poverty, HIV/AIDS, and extreme trauma they experienced. There was a lot of depression, but I felt their stories should be told, and so did they. When I returned to New York, I created several books and organized their stories for an exhibit.

Kiboko was started.

In 1996, I decided to start a 501 c 3 organization as a way of protecting my work and raising money. I kept thinking and going around and around in my head for a name associated with Africa. The name I finally came up with was Kiboko which means “hippo” in Swahili, after a somewhat scary experience with a couple of mating hippos in Botswana. I went to the Okavango Delta to take a camping safari. My tent was in an isolated area located as the last tent of the camp. It was the only tent available when I made the reservation at the last minute. It was early morning, like 2 am, when I heard sounds outside my tent. I could hear trees being snapped and the sound of what I thought was rain, but then there was grunting, which sounded like a wild animal. I remember seeing a lone hippo when I walked to my tent. I decided to stay in the tent, which was advised by guides and rangers of previous safaris. All the night long, the animals made loud noises keeping me awake.

The next morning, I carefully looked outside, where there was a large lake, and saw two mating hippos. When I got out of the tent, I noticed several trees had been bent over and some completely broken off, and there was feces sprayed all over the place, including on my tent. I was always very fond of hippos and found them amazing creatures. Later, I thought about the experience and realized Kiboko would be the perfect name for the new 501 c 3.

Before the Botswana hippo scare, I had a similar experience while camping in the Serengeti. I was camping, and a pride of lions came through the campsite along with some hyenas. I woke up to howling lions, a deafening sound, and the laughing sounds of hyenas. I was more scared of the lions, but nothing really happened, except I noticed our guides were all sleeping on the roofs of the Land Rovers. Later, we found out the armed ranger was sound asleep when the lions came through the campsite. This experience toughened me up, but I decided no more camping. I thought about calling the project Simba, but everyone was using that name, so I went with Kiboko, which was an original name at the time, but I noticed in a short time, everyone began to use it. In 1996 I started to incorporate Kiboko and filed for a 501 c 3 organization, and by 1999 was approved.

Kiboko Projects started to organize international workshops and exhibitions to focus on three countries: South Africa, Kenya, and Russia. The first project was in Kenya, where I returned to expand on the making of face masks and storytelling. I wanted to work more directly with youth in capturing their stories. At the time, I was very interested in the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Using the masks was fun and an interesting way for students to open up about their lives. There was a lot of stigma around the whole issue of HIV/AIDS. There were so many youths sick and dying from the dreaded disease. When in South Africa, youth would say a peer died from the flu instead of HIV/AIDS. For many of the youth it was very hard to talk about. I did the best I could in talking with them. Years later, when I returned to Kenya for another project, almost anyone could talk freely about HIV/AIDS. On returning to New York with a handful of stories, masks, film, and photographs, I reorganized them and traveled to St. Petersburg, Russia, where I introduced some of the projects to secondary school students. The stigmas were higher in St. Petersburg, and I had to be very careful of what I presented to the students.

My first trip to St. Petersburg was in 2001. I was tasked with creating a project for the celebration of the 2003 Tricentennial of St. Petersburg, Russia. I designed the project to use face masks, paintings, and photo diaries and focus on the history of St. Petersburg. Photography and videos were also part of creating the project. On completion of the workshops, I organized the project to travel to the US for an exhibition and then back to St. Petersburg for the celebration of the 2003 Tricentennial of St. Petersburg. An exhibition of the artwork, videos, and photographs was set up at the St. Petersburg Artists Exhibition Center in the historic area of downtown St. Petersburg. Several students from secondary schools, colleges, and universities came to see the exhibition. As a result of this success, we started several new projects in St. Petersburg and eventually in Veliky Novgorod.

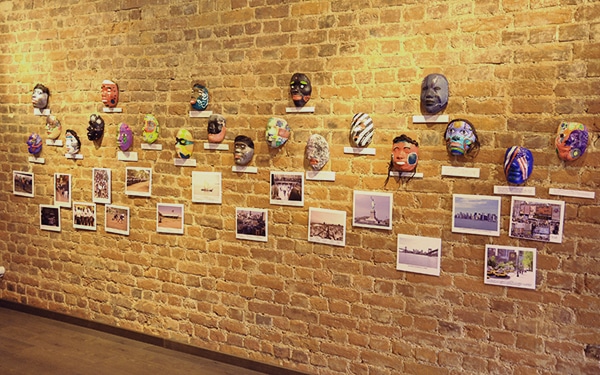

In 2003, Kiboko Projects traveled to Moi Forces Secondary School, Nakuru, Kenya, with a collection of paintings and drawings created by South Africans, Kenyans, and Russian youth. This artwork was presented to 16 selected Kenyan students. The goal for the Kenyans was to create a collection of masks, photo diaries, and a video project represent Kenyan culture. A Kenyan art teacher, the Kenyan students, and Jill and I worked every day for two weeks to create a project. The project resulted in a beautiful collection of hand-made and painted face masks. In addition, the students provided powerful stories about themselves and Kenyan culture. I showed them how to use video cameras. The result was a collection of masks and photo diaries made by each of the students.

When we returned to New York, we exhibited the collection of masks made by several schools and universities in the USA, Kenya, and Russia. Kiboko Projects received grants from several institutions, local art councils, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Grants and in-kind support led to several other projects in secondary schools throughout Kenya, USA, and St. Petersburg, Russia.

As the Kiboko Projects developed, I realized that they were more than an extracurricular activity for students. They were a real cultural exchange. I didn’t think life could get any better, and then I met Jill Raufman. I’ll let her tell the rest of the story.

Mark invited me to come with him to Kenya. I wasn’t sure—it had never occurred to me to travel to Africa. But I went, and it transformed my way of looking at things. In fact, it transformed my whole life.

Upon our return from Kenya, Mark and I started working on cultural exchange projects, which I had to squeeze in during evenings and days off from my 9-to-5 job in publishing. The first project we worked on together was at a girls’ secondary school in Nakuru—it was an exchange cultural/arts project with a school in NYC. I got to photograph, video, and interview many of the girls, heard their fears and dreams, and got to know them very well. During that same trip, we worked in Nairobi at the YMCA with an HIV-positive group, using artwork and masks, singing, poetry, and photo diaries for exchange. It was a world I had never experienced before, and I consider myself so blessed to have met everyone. Eventually, Mark established a nonprofit NGO (non-governmental organization), and Kiboko Projects was formed into a 501 c 3 organization. Mark was Artistic Director, and I became Executive Director.

In 2005, Jill and I started working with students at Eleanor Roosevelt High School in Manhattan. Projects were designed to include the school’s curriculums. Basically, the projects were structured in the same which was to include video, photography, and art. We added a new feature of video conferencing. We were able to use the internet to connect New York City students to schools in Kenya and, eventually, Russia. This feature allowed students to communicate on a weekly basis so they could learn about each other. We had them research specific topics beforehand so they could share and debate issues using the web conferencing. When these projects were finalized, we organized them into exhibitions and exchanged them between other schools, universities, and community centers in the US, Kenya, and Russia.

In 2016, we started collaborating with the Albert Einstein School of Medicine and a neighboring school named Pelham Lab High School, Bronx. We designed workshops to focus on social and community issues relating to health, and the idea of cultural humility. The medical school students mentored the high school students. We made a collection of face masks with the high school students while teaching them about health. When the Bronx part of the project was finished, we traveled with the nine medical school students and the artwork to Kalamba, Kenya. We designed workshops to include video conferencing and mask-making. The Einstein students served as mentors again, working directly with the Kenyan students.

The Einstein mentors and Kalamba Secondary School students were divided into groups and focused on social and political issues important to them. They made a collection of face masks and painted them. The Kenyan students organized day trips and took the medical school students around their community. The mentors visited the student’s families, medical clinics, and families in the community. Families shared their stories about their health issues and the treatments they were receiving. The Einstein students had the opportunity to learn about various illnesses and how medicine was practiced in a rural Kenyan community.

When we returned to New York, we curated an exhibition of photographs and masks and installed them in the exhibition cases at the library of the medical school. The library was open to both students and the public to view the exhibition.

In 2019, we decided to visit Kisoro, Uganda, and start a new project with Vision Secondary School. We met with the principal of the school to discuss the project and chose 8–10 students to participate. The focus would be health, the environment, and climate change. Covid disrupted the project until 2022 which is when we developed a new project called One Health and implemented the project at Lehman High School, in the Bronx. Albert Einstein medical students taught high school students about the concepts of One Health. The students used cameras to document various One Health issues in their communities and then designed and created a book about the work.

In 2023, we returned to Vision Secondary School, Kisoro, Uganda, to implement the ongoing project. We met with 8 students and showed them the book created by the Lehman High School students. We set up web conferencing between Lehman High School and Vision Secondary School so they could talk about the project. We designed specific videos relating to the project of One Health and the relationships between climate change, the environment, and health. We saw how much the Vision Secondary School students knew about these issues. We had them take photographs of their communities and write captions telling their stories about their own struggles with climate change, the environment, and how their health was affected. Using video, we interviewed the students about the photographs and issues relating to the One Health project. This year, 2023, we plan to travel back to Kisoro with a few medical school students to continue the project.